Tooling/Patternmaking

Patterns and Casting Flasks

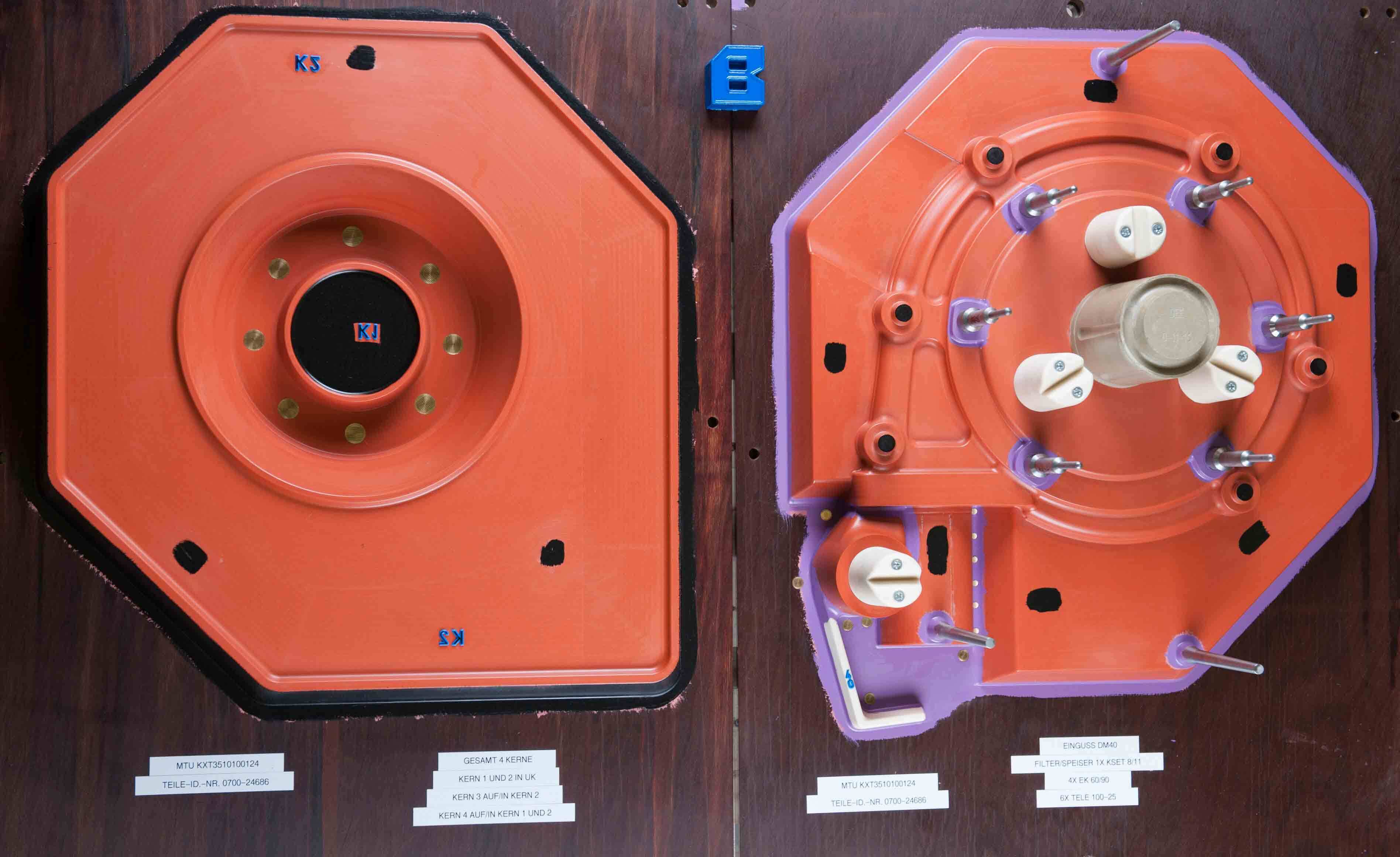

The primary tools needed in casting are the patterns, also known as models, and casting flasks or moulding boxes; together, these are used to create a mould out of sand with the necessary hollow spaces to produce a casting. Using technical drawings provided by the customer and/or computer files, the (theoretical) part shrinkage can be calculated. For these calculations, shrinkage in the longitudinal (x) direction differs from the transverse (y) direction, and (to make things even more complicated) the two forms can hinder each other. This is a problem that, above all, requires experience to conquer it – both in the simulation of these processes, as well as in the practical implementation. Even the casting temperature can change the results.

Toolmaking Is an Art

Tooling, in and of itself, is both an art and a science. In principle, it is a fundamental element of all sectors and for every material. And, despite all of the modern advantages offered with the advent of CAE, the critical factor for success is always the experience of a good team in tune with one another – one who knows the little quirks of their own production systems from years of experience. That’s why, at Brechmann-Guss, we rely on both: our design and production department uses CAD tools to design and dimension our models, and our in-house tooling and patternmaking team brings 140 years of experience to bear on the practical implementation.

The Right Pattern for Your Needs

With all this in mind, the material of the pattern and the expenditure are also directly related to the lot size (i.e., how many parts are needed). Depending on the necessary and agreed-upon service life, there are various options for the material used to make patterns: from lightweight engineering plastics, to “heavy” metal patterns made from aluminium or even from iron itself. The crux of the discussion is once again to be found in the details – there are easily machinable engineering plastics whose qualities make them easy to work with, which in turn decreases patterning costs. However, these inexpensive materials change their shape not only in response to millers and files, but also in response to the sand used to form the mould. A few abrasive sweeps of the forming sand, and the pattern is no longer within the given tolerances. More than one customer has thought they were getting a good deal on an inexpensive pattern from a competitor (or from an Eastern European supplier), only to discover with dismay after 1000 impressions that the cheaper pattern already needs to be replaced. Bad enough that he may not meet his delivery schedule, but the cost advantage has also gone down the drain.

Only after all of these considerations are complete can the chips start to fly – whether on a 3D CNC-milling machine (which is the standard first step at Brechmann-Guss to produce a pattern), or whether later in the process, perhaps after producing a test casting, from which a few fractions of a millimetre are ground down to obtain the exact dimensions specified in the protoype quality control report.

The Right Pattern for Your Needs

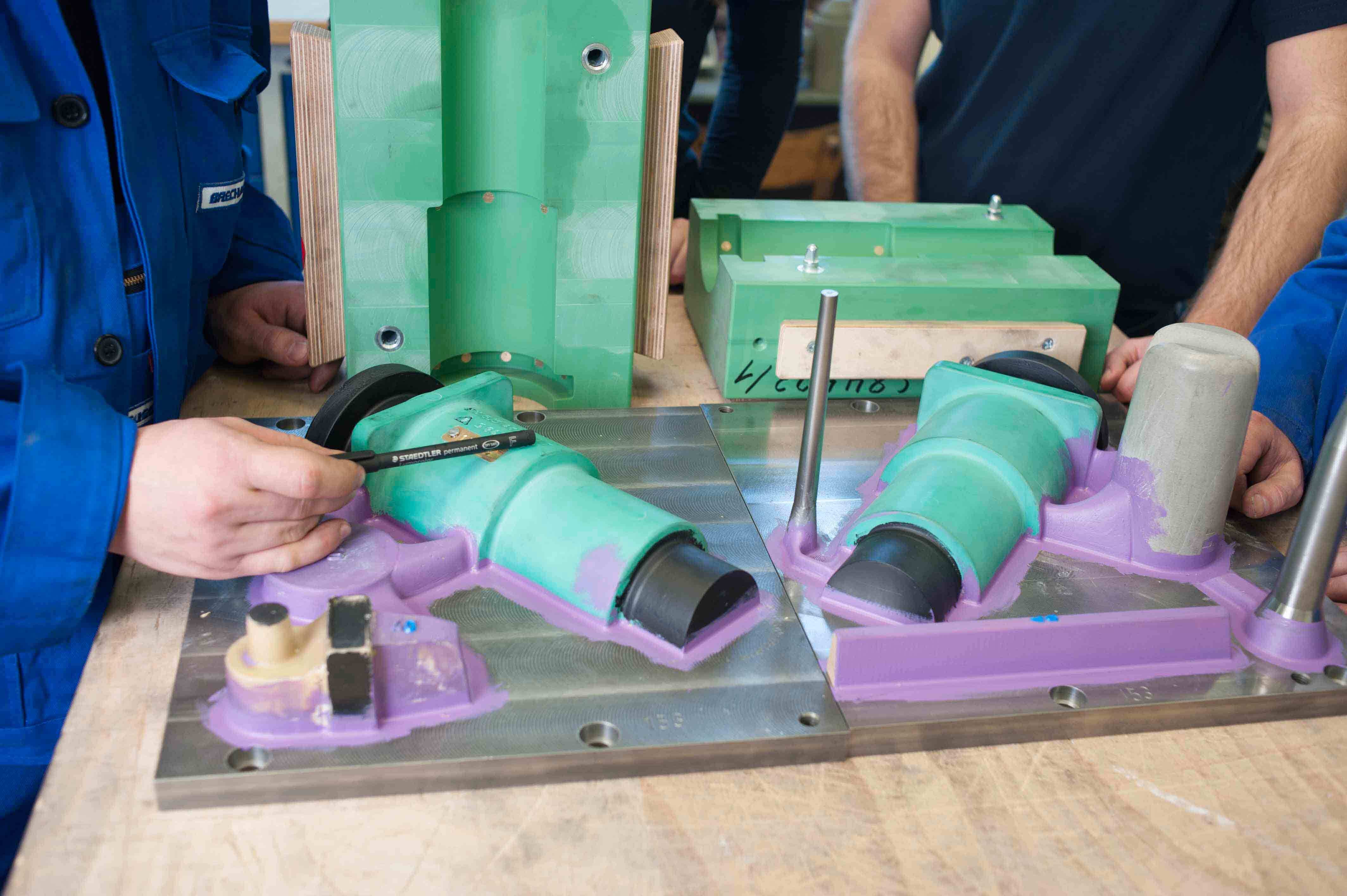

In addition to mocking up new or altered patterns, another important remit of patternmaking includes the refurbishing of models in use. This encompasses the minor and minimal repair of patterns, sprue and riser systems which are continually necessary; adding supplementary valves; changing out blocked lines; and all sorts of other minor adjustments and reconditioning from normal wear-and-tear.

Not least can this also include predictions, based on years of experience, of whether the mould itself will hold, or whether part of it may crack and break, and eventually become stuck in the casting – the so-called “breaking of cods”.

This phenomenon can occur when the sand is compressed around the pattern in the flask/moulding box; in the patterns, there are frequently impressions, indentations, or spaces between the moulding box and the pattern. Loose green sand is compressed into these indentations, resulting in bits of the sand mould that “stick out” into the hollow space – the so-called “cods”.